Exploring a Pictish Promontory Fort in Moray

In April 2018, Cathy MacIver of AOC’s Inverness Office was working with the Northern Picts and Comparative Kingship Projects from the University of Aberdeen at Burghead.

Since 2015 they have been working at Burghead, Moray on a major Pictish promontory fort that lies within the modern town. The immense size and complexity of the fort all point towards it being a major Pictish power centre. Antiquarian evidence for Burghead suggests a highly developed fortified site. It is likely that the promontory was a key component of the Pictish Kingdom of Fortriu, located in northern Scotland. Around 30 Class I symbol stones carved with bulls were discovered when the harbour and the planned village was built in 1805-09 and a deep well was discovered which still survives today. Unfortunately, much of the fort was destroyed during the construction of the planned village at the beginnings of the 19th century, but a small proportion of the upper and lower citadel survives at the seaward end.

Evaluative excavations from 2015-2017 within the Coastguard Station gardens revealed floor layers of buildings, a large midden and finds and deposits ranging from the 6th-10th centuries AD. These excavations revealed that, despite the modern impacts on the site, intact early medieval deposits survive in patches in the upper citadel, buried beneath extensive 19th century remodelling and midden deposits.

In April 2018, the team returned to investigate areas of the lower citadel and re-examine some of the areas explored during Alan Small’s excavations across the upper citadel wall in the 1960’s .

We wanted to understand more about the chronology of the enclosing elements of the fort and whether they were built as an integrated system or added to through time. The construction of the ramparts would also tell us about the resources utilised in their construction and what that implies about the social and political organisation in the early medieval period of Burghead. Understanding whether any intact deposits survived in the lower citadel was also important to inform us as to the level of preservation in different places across the site and what activities took place here.

Excavations in the lower citadel revealed some areas which had been heavily disturbed by modern intervention and other areas where preservation was better. The lower citadel wall appeared to have completely collapsed in many places with a substantial quantity of loose tumble and wall core spread on the inside of where the inner face once was. The excavations revealed the elaborate nature of the defences, with ramparts at least 7-8 m wide, up to 6 m high and made of quarried sandstone. Several courses at the very base of the inner wall face were identified but beyond that it was hard to confirm any more detailed information on construction due to the level of collapse.

Underneath the catastrophic collapse of the lower citadel wall a layer of preserved midden deposit was identified (below, right). Two bone pins, one bramble-headed and one mace-headed (below, left and centre), were identified within the midden. These finds have comparisons with 7th-9th century examples from the Brough of Birsay and Whithorn. A copper ring and a large iron nail/stake were also found in the midden layers. These middens were also filled with animal and some fish bone which could give us good economic indicators of the early medieval period here. Several possible structures were identified elsewhere in the interior of the lower citadel.

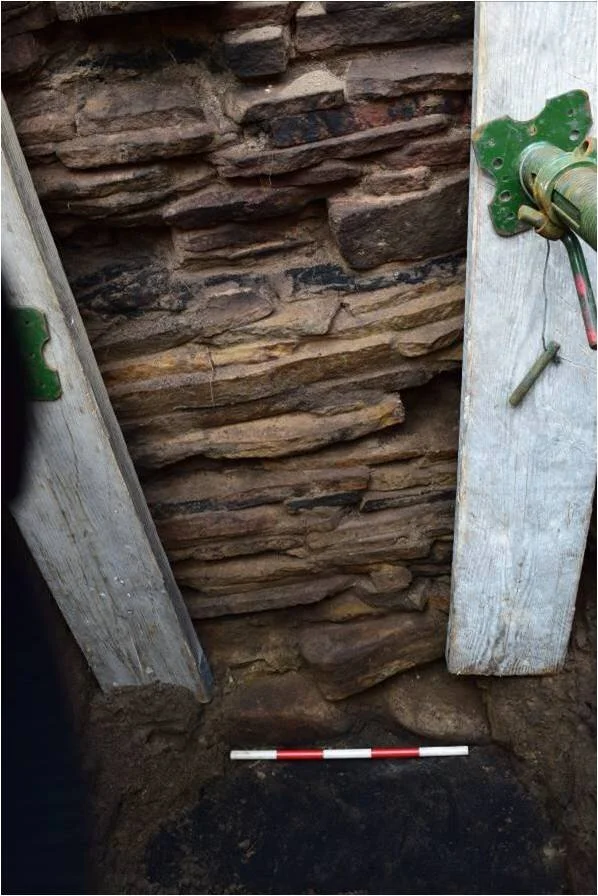

Work in the upper citadel concentrated on re-excavating one of Alan Small’s trenches across the wall. Work in this area revealed a lovely inner face with intact burnt timbers surviving to a height of about 1.6m. Unlike in the lower citadel, here the preservation was good enough to confirm that the rampart had been constructed of quarried sandstone combined with timber-lacing of plank and beam construction. The charred timber elements could be identified running both through the wall and horizontally along the length of the wall face. Across the face the stones were visibly reddened and heat affected, implying a large burning event, related to destruction of the wall. The inner face, although relatively well preserved, is situated only a few metres away from an eroding cliff face, making excavation and recording of this feature while it still survives a high priority.

All these features merit further investigation and we hope to return next year to find out more. Meanwhile, a programme of post-excavation work is examining samples from the midden, the animal bone and finds. Crucial layers are being dated to understand the construction and use of the site. Initial dating results demonstrate that the site was likely first in use in the 6th century AD and went out of use in the early to mid 10th century AD. The midden deposits in the lower citadel date to the 7th-8th centuries AD which fits with the type of finds retrieved from it. Destruction layers in the upper citadel produce a later range of dates closer to the 9th-10th century AD.

You can find out more about this work here: